Brexit: A new hope for the UK’s environment?

As some of the dust starts to settle (or not…) on the results of last week’s referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU, I’m clearly not the only environmental writer who’s been thinking day and night about the implications.

Readers of my chapter in Chalk Stream Fly Fishing (2012) may recall that I’m very much in favour of a system of supranational checks and balances on issues as fundamental as the health of the environment which transcends national boundaries yet still supports every aspect of our lives. When properly implemented into national law, the EU’s environmental directives have proved an excellent mechanism for identifying objective benefits, turning short-term political footballs into helpful long-term strategies, and keeping national governments honest, on both sides of the political spectrum.

For instance, the Water Framework Directive has enabled the clear public benefit of healthy rivers (and bugs, and birds, and fish) to be enshrined in UK law, with deadlines for meeting measurable quality improvements, and fines for not achieving these. It also mandates active involvement of stakeholders, and has given interested NGOs the right to challenge government for not taking these requirements seriously enough in their River Basin Management Plans. This has already resulted in several rounds of small but significant government funding for third sector organisations, mainly Rivers Trusts and Wildlife Trusts, to deliver river-related improvements with very high cost efficiencies in every catchment in the UK.

In these new times of great uncertainty, almost the only sure bet is that environmental issues and ecosystem services won’t be at the top of most politicians’ to-do lists or budget spreadsheets. Yet, now more than ever, the natural world really does matter. It will underpin every part of our future national policies – on farming, flood defence, clean air and water supplies, even religious and cultural inspiration – for generations to come. And it’s our responsibility to make sure that this message is heard.

So, leaving personal shock aside, what can we do as calm environmental professionals to help a smoother transition into the brave new world of post-Brexit Britain? I’ve started compiling this short aide-memoire of my own, and hope to add to it as our situation becomes clearer and our national conversation develops…

1: Be clear that environmental protection must remain enshrined in law

As Tony Juniper wrote before the referendum, EU directives have created the context for most of the UK’s most valuable environmental protections.

SSSIs, SACs, the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) and recent regulations on the sale and import of invasive non-native species – all of these (and many more) provide clear benefits for everyone in our society and transnational ecosystem. As environmentalists, we must be very clear in our messaging to our elected representatives that WFD and other targets should be remain in place. Existing high standards of protection should be retained, enhanced (indeed perhaps shadowing future best practice as the EU’s environmental regulations continue to develop) and certainly not discarded as ‘green crap’ in some future cost-saving ‘bonfire of the directives’.

Further reading:

- Tony Juniper: Europe, the environment, and the smell of 1973

- Mark Lloyd: What does the EU referendum mean for fish, fishing and much more?

2: Maintain the Catchment Based Approach to river management

Our natural world knows no political borders – indeed the transnational nature of great European rivers like the Rhine and Danube provided the inspiration for many of the EU’s highest environmental standards.

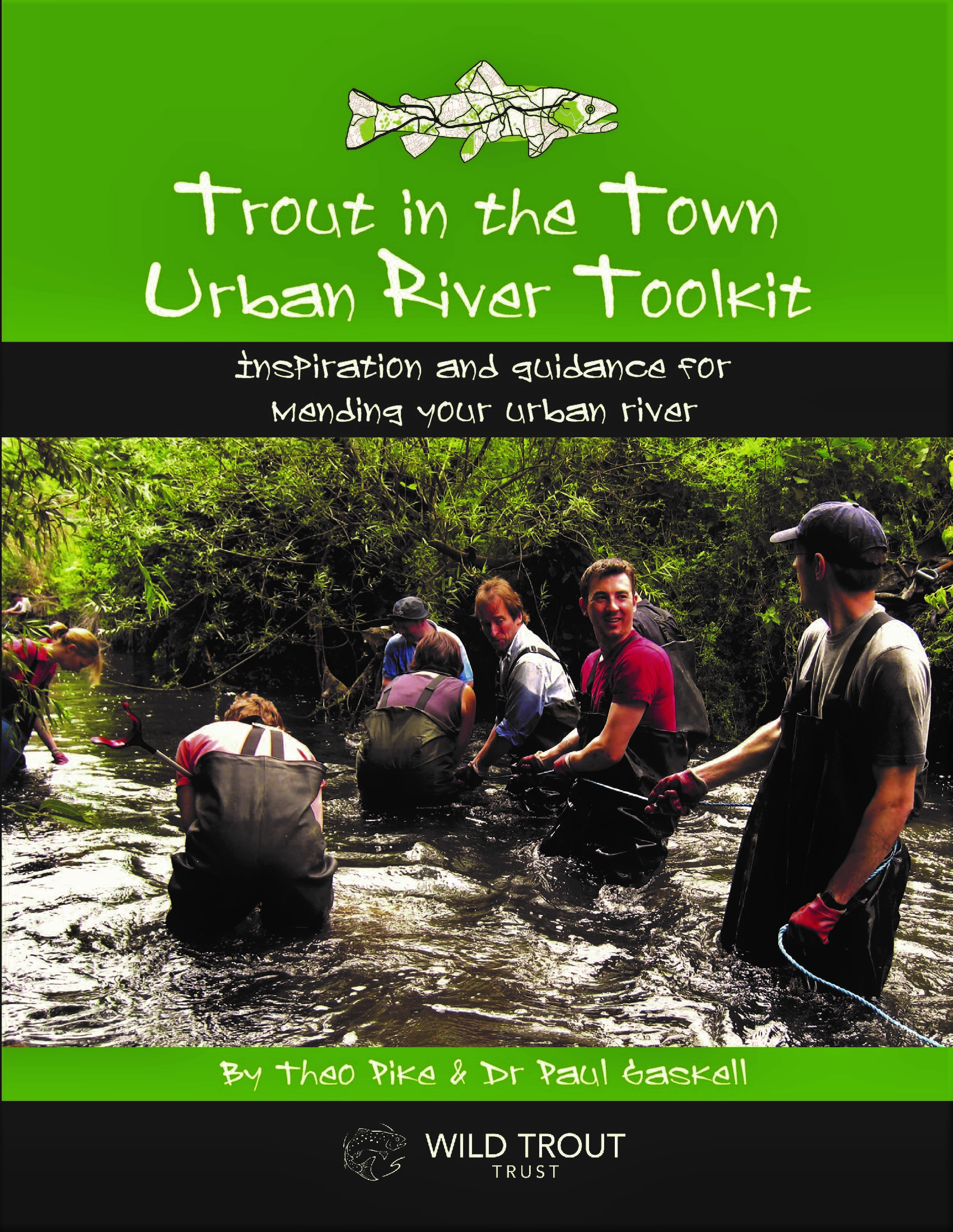

Here in the UK, the Catchment Based Approach has proved to be a practical and intuitive framework for managing the health not just of our waterways, but all our urban and rural surroundings. As a grassroots mechanism for delivering the Water Framework Directive, it empowers local stakeholders to take real ownership of the health of the places where they live. So this highly democratic partnership working has already harnessed startling reserves of local support and goodwill, producing tangible results year on year.

As the terms of Brexit take shape, river restorationists must ask Defra and the Environment Agency to commit to the future of local catchment partnerships, with secure long-term funding to enable cost-effective management of flooding, invasive non-native species, healthy soils and many other urgent issues. Failure to maintain this strategic investment in our river catchments will almost certainly prove to be a false economy in a world where the effects of climate change are already becoming clear. As many commentators have rightly pointed out, it’s exponentially cheaper to invest in a healthy environment now, than to have to pay for picking up the pieces when everything goes wrong at some inconvenient time in the future.

Further reading:

- Laurence Couldrick, WRT: Moving forward as one

- WaterLIFE: Enhancing the impact of local community groups through catchment partnerships

3: Devise robust new environmental mechanisms for the future

It’s true to say that not all European legislation has resulted in the best possible outcomes – Common Agricultural Policy subsidies, for example, a situation which George Monbiot has addressed in this article, among many others. Similarly, as S&TC’s recent work on aquatic invertebrates has shown, SSSI and SAC designation has spectacularly failed to protect the health of some of our most iconic rivers (if you can find more freshwater shrimp in the urban Wandle than the rural upper Itchen, something has clearly gone badly wrong).

Despite the risks, Brexit could provide us with an astonishing chance to examine our whole suite of environmental funding and designation mechanisms for fitness for purpose, and perhaps enhance or revision them with even better approaches for the future (for instance, the principles of rewilding could offer real economic benefits).

If properly handled, there’s every chance that this could represent an incredible creative opportunity – an inspiring new hope for our common environment, and a possibility which we must all be prepared to grasp.

Further reading:

- S&TC’s Riverfly Census

- Wildlife and Countryside Link: The UK Government’s 25 Year Plan for Nature

- Rory Stewart: Realism, humility, honesty, confidence and identity (a new land ethic for post-Brexit Britain?) (Full Hansard report here)

- National Trust: A call for major reform of farming subsidies

- The House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee: The Future of the Natural Environment after the EU Referendum (disappointingly “within existing comfort zones” according to Monbiot – read his full submission here)

- People Need Nature: A Pebble in the Pond: Opportunities for farming, food and nature after Brexit

- Patrick Begg: How a new Natural Infrastructure Scheme could work

Update: March 2017: Now that the crucial Article 50 has been invoked, environmental NGOs and concerned citizens must continue to do everything possible to ensure that the natural world takes its rightfully central place in negotiations about the future of our country.

Because as the dust settles (or not…) one thing is certain: sometime, somehow, a new environmental settlement will also eventually be needed.

(Photo: South East Rivers Trust)

A nice positive message, thank you..

Wise and thought-provoking stuff, Theo. Could we be seeing the political equivalent of punctuated equilibrium here?

Both major parties in meltdown, past mendacities coming home to roost – maybe there is room for a new approach? I am an incurable optimist….

Given Boris Johnson’s father, who was an MEP with top notch environmental credentials, and Exmoor upbringing, Boris could be a sensible choice for PM to help our cause.

All environmental organisations need to come together to be truly representative so that they can; properly influence government, big business and their consumers and develop a fighting fund/legal arm, like the AT’s so that they can take legal proceedings. That way we will be noticed for ever.

Theo. Fine in principle just beware ‘framing’ of the issues. The neighbours of water are often, if not always, farmers (bar the Wandle et al) and engaging them at grassroot level is key. How you communicate with them will involve more nuanced common ground outcomes and less use of the words ‘regulation’, ‘rewilding and Monbiot’.in the same sentence.

Example http://www.countryfile.com/explore-countryside/wildlife/what-do-farmers-think-rewilding

With you all way. Rob Yorke

The environment will be greatly helped past-brexit by no longer allowing mass immigration and (over) population rise to continue. Less built-up areas are hopefully going to be needed and developed which means more room for the natural world.

Well said, Theo. From a personal perspective, last Thursday/Friday was a black time but good messages from you: time now to get on.

Sound words. The desire of many anglers is to help improve our rivers etc. The strong mandate ,if I can use such a term, that organisations like The Wild Trout Trust retains, remains in place & we should look for ways to build a critical mass of opinion that can’t be ignored.

The UK was set to wriggle out of another WFD deadline with appallingly low ambition but our agencies have duties under domestic legislation to improve and develop. I’ve never liked the idea that the European Commission should be forcing us to look after our land, water and air. We have the wrong people in charge if that is the case and I know we have the wrong people in charge, some of whom jumped ship from these agencies to the trusts when they could.

Three excellent and well-reasoned points thanks Theo.

[…] Theo Pike – A new hope for the UK’s environment? […]