Reinventing Slovenia

It’s genuinely been years and years since I fished in Slovenia.

Leafing back through my fishing diary, I can vividly remember exploring the Soca for the first time in 2003, and the Baca and Idrijca in 2004. Scrambling over white limestone boulders under fantastical mountain peaks, stalking evanescent trout and grayling in water as clear as air, this was dreamlike fishing in a landscape still stained and haunted by the bloodiest battles of the First World War. Nothing could have stopped me going back to the Baca, Idrijca, Lepena and upper Soca in 2006. But that’s when disillusionment hit.

On a sunny September afternoon, we’d stopped for lunch high up on the Slovenian Fisheries Institute beats of the Soca where, I’d been assured, all the fish were wild (if not necessarily native, but that’s another story) and no stocking took place. While Sally unwrapped the sandwiches, I wandered over to the bridge, and looked down into glacial blue-green water.

Where I’d expected to see a shining limestone bed, with maybe a few singleton trout and a dozen grayling shimmering in a half-seen mid-water shoal, the river was black with fish. Browns and rainbows, all of a size, about 3lbs, milling around, chasing each other’s tails. I was mesmerised: either the upper river was unbelievably productive, or a stocking truck had just dumped its entire cargo into the gorge. After lunch, I left my rod in the car, clambered down the rock revetments, and waded out to take a closer look. Far from dashing away in natural terror, 500 tame stockies turned as one, and started swimming towards me.

I won’t say I actually ran out of the water, but I definitely put lots of distance between myself and the Slovene fishing scene for almost ten years. Fishing the Soca wasn’t cheap: for wild trout and mountains, Austria honestly felt like a better idea.

In the meantime, several good fishing buddies went out and discovered the astonishing Julian Alps for themselves, and so did many other international fly-fishers and film-makers. Between us we winced at the day ticket prices, consulted cagey experts, and deduced that the great north-western rivers of Slovenia had basically been sacrificed to the need for a country the size of Wales to earn some kind of cross-border income stream from the natural assets God had given it. Even if that involved heavy stocking to counteract the reluctance of the native marmoratus trout to eat dry flies in daylight, or replace whole populations of Soca grayling wiped out by natural spates of fine-grained limestone scourings from the mountains, we kinda understood.

But I still stayed away.

That’s until this autumn. In the years between, my good pal (and professional freelance fishing photographer) Duncan had been steadily renovating a beautiful old farmhouse on the Pokljuka plateau in the Triglav National Park, 30 bends up the mountain road from Bohinja Bistrica, and now he was ready to start showing it off to his fishing pals. He’d also presented me with more than enough evidence to suggest that the rivers on the Sava side of the mountains weren’t quite as heavily stocked as the Soca system. All in all, it finally looked like time to stand up to that old trauma.

By the time we landed at Ljubljana, heavy rain had blown out most of the rivers we’d been planning to fish – but a long drive and accurate intel from Matej at Fauna Bled sent us far to the south-east to explore an area which hadn’t been so badly deluged, and the headwaters of the Krka in a village of the same name.

“With so many other rivers high and unfishable, you may find a lot of fishermen on the Krka,” Matej had warned us. Peering over the village bridge, we found two of them there already, throwing big foam strike indicators into shrunken pools and runs. We drove downstream, along a farm track with wheel ruts so deep we had to straddle them into the lush meadows of dandelions, oregano, mint and autumn crocuses on either side, before parking up in a little copse of ash and hazel on a bluff above the river. Flocks of house martins swirled around the bankside willows and alders, feasting on needle flies disturbed by a sudden downpour. When the rain eased off, the rises began, splashy and eager, easy to mistake at first for big drips from the trees…

Surrounded by the rolling maize fields and forests of Dolenjska province, the Krka displays a mysterious mix of chalkstream, karst and spate runoff characteristics. Industry has also left its mark in the form of many weirs and mills, and investigations linked to the European Water Framework suggest that the river’s aquifer is perilously contaminated with a whole cocktail of pesticides, most likely from intensive communist-era farming.

The Krka’s karst springs below Krska Jama produce water so supersaturated with calcium that the river is continually depositing ridges of tufa and travertine down its wooded canyon in the Zuzemberk geological fault. As you retrieve your line, the hardness of the water feels weirdly soapy between your fingertips, and spooky mists crawl out of steep temperature gradients between the air and the river, dissolving and reappearing so suddenly it’s possible to lose sight of your fly on the end of a long cast.

All those limestone nutrients also encourage rope-thick growths of filamentous algae – which can seem welcome enough when they’re doing the same kind of habitat jobs as ranunculus, as well as offering close cover for anglers stalking wary fish with short-range ultralight tackle.

They’re suddenly more of a problem when good trout after good trout crash-dives into the green stuff, leaving you with nothing but tippet corkscrewed round half a pound of crud, and a once-dry fly crumpled somewhere in its depths. But after finding a stretch of faster-flowing water and a full-on spinner fall, we both caught chunky little wild browns and rainbows into darkness on dries… and isn’t that really the best you can ask of a totally new river in a corner of a foreign field you’ve never seen before?

For the rest of the trip, we drove long distances, ate late-night pizza, pored over maps, drank lots of coffee in the mornings, and explored other rivers that I’m not quite ready to mention by name, here on the open internet.

On the other hand, I’m happy to admit that all traces of post-traumatic stockie disorder are history. As of now, I’m right back in the Slovene wild fish programme.

(Photos 1, 3 and 5: Duncan Soar)

[…] Rising at St Aldhelm’s Well near Doulting, the Sheppey flows down from the Mendips to meet the main River Brue on the Somerset Levels through a pretty, winding limestone valley that often reminds me of somewhere in Slovenia. […]

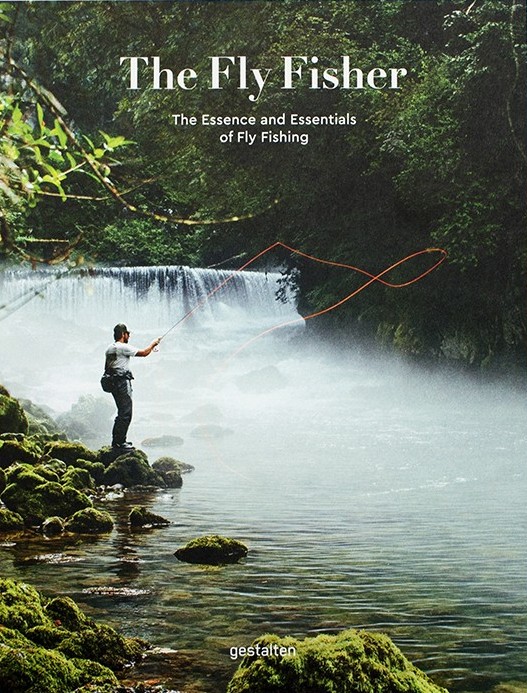

[…] addition to the Club’s Library, we somehow persuaded the talented fly-fishing photographer (and my own good fishing pal!) Duncan Soar to shoot the books on location – and his luminous photos now take pride of […]